How Might Service On The Slave Patrols Have Affected Plantation-belt Yeomen In The Antebellum South?

When the Georgia Trustees outset envisioned their colonial experiment in the early 1730s, they banned slavery in guild to avoid the slave-based plantation economy that had developed in other colonies in the American S. The allure of profits from slavery, however, proved to be too powerful for white Georgia settlers to resist. Past the era of the American Revolution (1775-83), slavery was legal and enslaved Africans constituted nearly half of Georgia'south population.

Although the Revolution fostered the growth of an antislavery movement in the northern states, white Georgia landowners fiercely maintained their commitment to slavery even as the war disrupted the plantation economy. In fact, Georgia delegates to the Continental Congress forced Thomas Jefferson to tone down the critique of slavery in his initial draft of the Announcement of Independence in 1776. Likewise, at the constitutional convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1787, Georgia and Due south Carolina delegates joined to insert clauses protecting slavery into the new U.Southward. Constitution. In subsequent decades slavery would play an ever-increasing function in Georgia'southward shifting plantation economic system.

Cotton and the Growth of Slavery

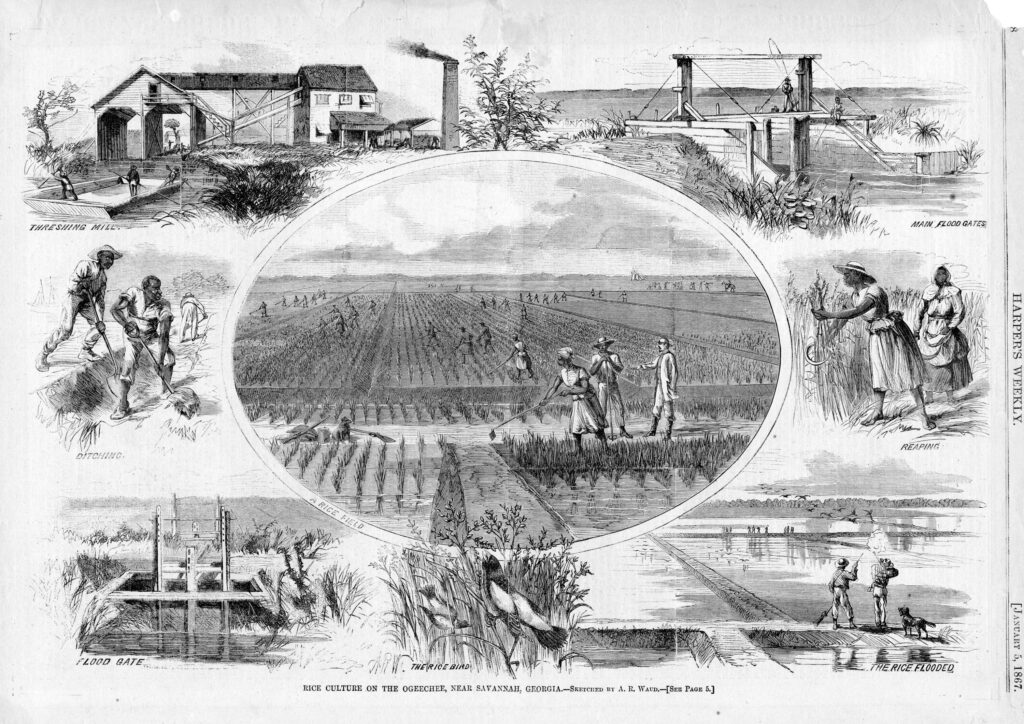

For almost the entire eighteenth century the production of rice, a crop that could exist commercially cultivated only in the Lowcountry, dominated Georgia's plantation economy. During the Revolution planters began to cultivate cotton fiber for domestic use. After the war the explosive growth of the textile manufacture promised to plough cotton into a lucrative staple crop—if only efficient methods of cleaning the tenacious seeds from the cotton fibers could exist adult.

From Harper's Weekly

Past the 1790s entrepreneurs were perfecting new mechanized cotton wool gins, the most famous of which was invented past Eli Whitney in 1793 on a Savannah River plantation owned by Catharine Greene. This technological advance presented Georgia planters with a staple crop that could be grown over much of the country. As early every bit the 1780s white politicians in Georgia were working to larn and distribute fertile western lands controlled by the Creek Indians, a process that connected into the nineteenth century with the expulsion of the Cherokees. Past the 1830s cotton plantations had spread across near of the state.

As was the case for rice product, cotton planters relied upon the labor of enslaved African and African American people. Accordingly, the enslaved population of Georgia increased dramatically during the early decades of the nineteenth century. In 1790, simply before the explosion in cotton production, some 29,264 enslaved people resided in the state. In 1793 the Georgia Assembly passed a constabulary prohibiting the importation of captive Africans. The law did not become into result until 1798, when the state constitution also went into effect, but the measure was widely ignored by planters, who urgently sought to increase their enslaved workforce. By 1800 the enslaved population in Georgia had more doubled, to 59,699, and by 1810 the number of enslaved people had grown to 105,218.

The 48,000 Africans imported into Georgia during this era deemed for much of the initial surge in the enslaved population. When Congress banned the African slave trade in 1808, even so, Georgia's enslaved population did not decline. Instead, the number of enslaved African Americans imported from the Chesapeake's stagnant plantation economic system every bit well as the number of children born to enslaved mothers connected to outpace those who died or were transported from Georgia. In 1820 the enslaved population stood at 149,656; in 1840 the enslaved population had increased to 280,944; and in 1860, on the eve of the Ceremonious War (1861-65), some 462,198 enslaved people constituted 44 percent of the state's total population. Past the terminate of the antebellum era Georgia had more enslaved people and slaveholders than whatever state in the Lower South and was second only to Virginia in the South as a whole.

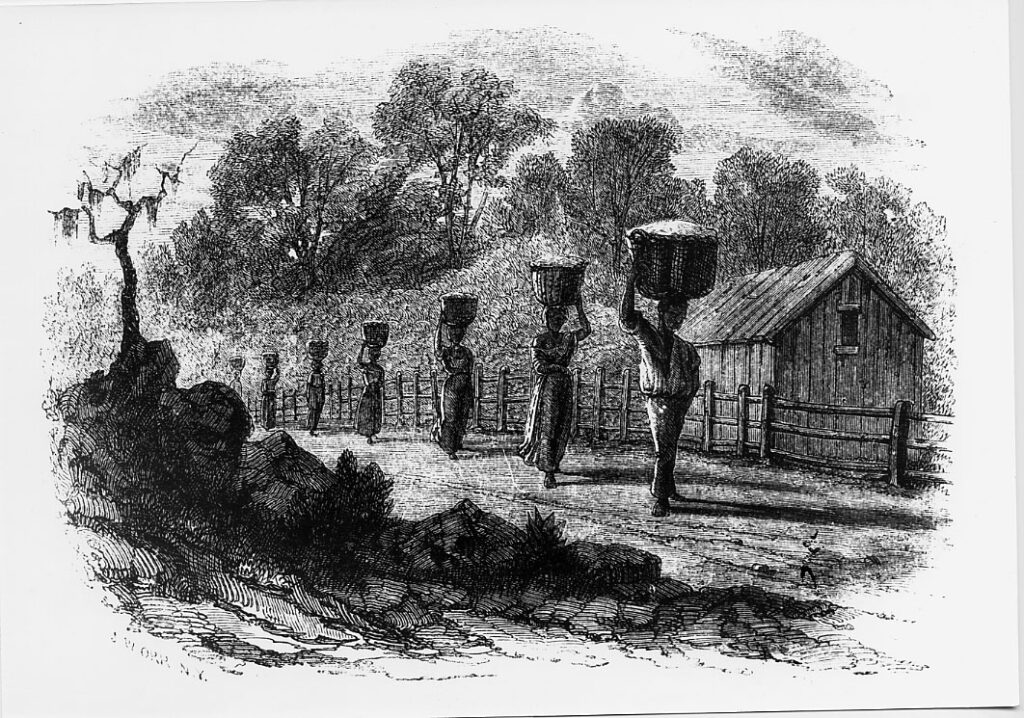

From Harper'southward New Monthly, March 1854

The lower Piedmont, or Black Belt, counties—and then named after the region's distinctively dark and fertile soil —were the site of the largest, most productive cotton fiber plantations. Over the antebellum era some two-thirds of the state'southward total population lived in these counties, which encompassed roughly the middle third of the state. By 1860 the enslaved population in the Black Belt was ten times greater than that in the littoral counties, where rice remained the most important crop.

Slaveholders

Although slavery played a ascendant economic and political part in Georgia, most white Georgians did not claim people as property. In 1860 less than one-3rd of Georgia's developed white male population of 132,317 were slaveholders. The percentage of free families belongings people in slavery was somewhat higher (37 pct) only yet well short of a bulk. Moreover, only 6,363 of Georgia's 41,084 slaveholders enslaved xx or more than people. The planter aristocracy, who fabricated upwards merely xv percentage of the country'due south slaveholder population, were far outnumbered past the 20,077 slaveholders who enslaved fewer than half dozen people. In other words, only one-half of Georgia'southward slaveholders enslaved more than a handful of people, and Georgia's planters constituted less than five per centum of the state's developed white male population.

These statistics, withal, exercise not reveal the economical, cultural, and political forcefulness wielded past the slaveholding minority of the population. Slaveholders controlled not only the best country and the vast majority of personal property in the state merely likewise the state political organisation. In 1850 and 1860 more than two-thirds of all state legislators were slaveholders. More than hit, almost a third of the state legislators were planters. Hence, even without the cooperation of nonslaveholding white male voters, Georgia slaveholders could dictate the state's political path.

Courtesy of New York Historical Guild

As it turned out, slaveholders expected and largely realized harmonious relations with the remainder of the white population. During ballot season wealthy planters courted nonslaveholding voters past inviting them to celebrations that mixed speechmaking with arable supplies of nutrient and beverage. On such occasions slaveholders shook easily with yeomen and tenant farmers as if they were equals. Nonslaveholding whites, for their part, frequently relied upon nearby slaveholders to gin their cotton and to assist them in bringing their ingather to market place. These political and economic interactions were further reinforced past the mutual racial bail among white Georgia men. Sharing the prejudice that slaveholders harbored against African Americans, nonslaveholding whites believed that the abolition of slavery would destroy their ain economic prospects and bring catastrophe to the state as a whole.

Propping up the establishment of slavery was a judicial organization that denied African Americans the legal rights enjoyed by white Americans. Since the colonial era, children born of enslaved mothers were deemed chattel, doomed to "follow the condition of the mother" irrespective of the begetter'southward status. Georgia constabulary supported slavery in that the state restricted the right of slaveholders to free individuals, a mensurate that was strengthened over the antebellum era. Other statutes fabricated the circulation of abolitionist material a capital law-breaking and outlawed literacy and unsupervised associates amongst enslaved people. Although the law technically prohibited whites from abusing or killing enslaved people, information technology was extremely rare for whites to be prosecuted and convicted for these crimes. The legal prohibition confronting slave testimony virtually whites denied enslaved people the ability to provide testify of their victimization. On the other hand, Georgia courts recognized confessions from enslaved individuals and, depending on the circumstances of the case, testimony against other enslaved people.

Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada

The relative scarcity of legal cases concerning enslaved defendants suggests that almost slaveholders meted out discipline without involving the courts. Slaveholders resorted to an assortment of physical and psychological punishments in response to misconduct, including the utilize of whips, wooden rods, boots, fists, and dogs. The threat of selling an enslaved person away from loved ones and family members was peradventure the most powerful weapon bachelor to slaveholders. In general, penalisation was designed to maximize the slaveholders' power to gain profit from slave labor. Evidence also suggests that slaveholders were willing to employ violence and threats in guild to coerce enslaved people into sexual relationships.

Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration

Over the antebellum era whites continued to utilise violence against the enslaved population, but increasingly they justified their oppression in moral terms. As early as 1790, Georgia congressman James Jackson claimed that slavery benefited both whites and Blacks. The expanding presence of evangelical Christian churches in the early nineteenth century provided Georgia slaveholders with religious justifications for man chains. White efforts to Christianize the slave quarters enabled slaveholders to frame their ability in moral terms. They viewed the Christian slave mission every bit prove of their ain adept intentions. The religious instruction offered by whites, moreover, reinforced slaveholders' authority by reminding enslaved African Americans of scriptural admonishments that they should "give unmarried-minded obedience" to their "earthly masters with fear and trembling, equally if to Christ."

This melding of organized religion and slavery did non protect enslaved people from exploitation and cruelty at the hands of their owners, merely information technology magnified the role played by slavery in the identity of the planter elite. In 1785, just before the genesis of the cotton fiber plantation organization, a Georgia merchant had claimed that slavery was "to the Trade of the Country, as the Soul [is] to the Body." Lxx-five years later Georgia politician Alexander Stephens noted that slavery had go a moral as well every bit an economical foundation for white plantation culture. The "corner-stone" of the South, Stephens claimed in 1861, merely subsequently the Lower S had seceded, consisted of the "great physical, philosophical, and moral truth," which is "that the negro is not equal to the white homo; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition."

Slaves

Depending on their place of residence and the personality of their slaveholders, enslaved Georgians experienced tremendous variety in the atmospheric condition of their daily lives. Although the typical (median) Georgia slaveholder enslaved six people in 1860, the typical enslaved person resided on a plantation with twenty to twenty-nine other enslaved African Americans. Almost half of Georgia's enslaved population lived on estates with more thirty enslaved people. Almost enslaved Georgians therefore had access to a community that partially offset the harshness of bondage. Testimony from enslaved people reveals the huge importance of family unit relationships in the slave quarters. Many were able to alive in family units, spending together their limited time abroad from the enslavers' fields. Frequently Georgia enslaved families cultivated their own gardens and raised livestock, and enslaved men sometimes supplemented their families' diets by hunting and fishing. Christianity also served as a pillar of slave life in Georgia during the antebellum era. Different their enslavers, enslaved African Americans drew from Christianity the message of Blackness equality and empowerment. In the early on nineteenth century African American preachers played a significant role in spreading the Gospel in the quarters.

Photograph by Wikimedia

Throughout the antebellum era some thirty,000 enslaved African Americans resided in the Lowcountry, where they enjoyed a relatively high degree of autonomy from white supervision. Well-nigh white planters avoided the unhealthy Lowcountry plantation environment, leaving big enslaved populations under the supervision of a small group of white overseers. Enslaved workers were assigned daily tasks and were permitted to leave the fields when their tasks had been completed. Enslaved laborers in the Lowcountry enjoyed a far greater degree of command over their time than was the case across the rest of the state, where they worked in gangs under directly white supervision. The white cultural presence in the Lowcountry was sufficiently small for enslaved African Americans to retain meaning traces of African linguistic and spiritual traditions. The resulting Geechee culture of the Georgia coast was the analogue of the amend-known Gullah culture of the Southward Carolina Lowcountry.

The urban surroundings of Savannah likewise created considerable opportunities for enslaved people to live away from their owners' watchful optics. Enslaved entrepreneurs assembled in markets and sold their wares to Black and white customers, an economic system that enabled some individuals to aggregate their own wealth. A number of enslaved artisans in Savannah were "hired out" by their owners, meaning that they worked and sometimes lived away from their enslavers. Savannah'due south taverns and brothels also served as meeting places in which African Americans socialized without owners' supervision. This cultural autonomy, even so, was never complete or secure.

The rice plantations were literally killing fields. On one Savannah River rice plantation, bloodshed annually averaged x percent of the enslaved population between 1833 and 1861. During cholera epidemics on some Lowcountry plantations, more than half the enslaved population died in a affair of months. Babe mortality in the Lowcountry slave quarters also greatly exceeded the rates experienced by white Americans during this era. In addition to the threat of disease, slaveholders frequently shattered family and community ties by selling members away. More than 2 million enslaved southerners were sold in the domestic slave trade of the antebellum era.

Three-quarters of Georgia's enslaved population resided on cotton fiber plantations in the Blackness Belt. They typically experienced some degree of community and they tended to exist healthier than enslaved people in the Lowcountry, simply they were also surrounded by far greater numbers of whites. Some i-fifth of the state's enslaved population was endemic by slaveholders who enslaved fewer than 10 people. These enslaved people doubtless faced greater obstacles in forming relationships outside their enslavers' purview. Any their location, enslaved Georgians resisted their enslavers with strategies that included overt violence against whites, flight, the devastation of white property, and deliberately inefficient work practices. White southerners were worried plenty virtually slave revolts to enact expensive and unpopular slave patrols, groups of men who monitored gatherings, stopped and questioned enslaved people traveling at nighttime, and randomly searched enslaved families' homes. Enslaved Georgians experienced hideous cruelties, but white slaveholders never succeeded in extinguishing the human being chapters to covet freedom.

Secession, the Civil State of war, and the Finish of Slavery

By the late 1820s white slaveholders in Georgia—like their counterparts beyond the South—increasingly feared that antislavery forces were working to liberate the enslaved population. The publication of slave narratives and Uncle Tom's Cabin in 1852 farther agitated abolitionist forces (and slave owners' anxieties) by putting a human face on those held by slavery. In the months post-obit Abraham Lincoln'due south election as president of the United States in 1860, Georgia's planter politicians debated and ultimately paved the fashion for the land's secession from the Union on January 19, 1861. Statesmen similar Senator Robert Toombs argued that secession was a necessary response to a longstanding abolitionist campaign to "disturb our security, our tranquillity—to excite discontent between the different classes of our people, and to excite our slaves to insurrection." Lincoln's election, co-ordinate to these politicians, meant "the abolitionism of slavery," and that act would be "one of the direst evils of which the listen can conceive."

Ironically, when Georgia's leading planter politicians led their state out of the Marriage, they and their young man secessionists gear up in motion a chain of destructive events that would ultimately fulfill their prophecies of abolitionism. The arrival of Union gunboats along the Georgia coast in belatedly 1861 marked the beginning of the end of white ownership of enslaved African Americans. Equally hundreds of enslaved people from the Lowcountry fled beyond enemy lines to seek sanctuary with Spousal relationship troops, Georgia slaveholders attempted to motion their bondsmen to more than secure locations.

From Harper'south Weekly

By fall 1864, however, Union troops led past General William T. Sherman had begun their subversive march from Atlanta to Savannah, a armed services accelerate that effectively uprooted the foundations for plantation slavery in Georgia. Amidst the anarchy and misfortunes unleashed past the war, enslaved African Americans too every bit white slaveholders suffered the loss of property and life. In the wake of war, however, white and Blackness Georgia residents articulated opposite views nearly emancipation. The old slaveholders bemoaned the demise of their plantation economy, while the freedpeople rejoiced that their bondage had finally ended.

How Might Service On The Slave Patrols Have Affected Plantation-belt Yeomen In The Antebellum South?,

Source: https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/slavery-in-antebellum-georgia/

Posted by: royliting.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Might Service On The Slave Patrols Have Affected Plantation-belt Yeomen In The Antebellum South?"

Post a Comment